There’s no shortage of advice when it comes to how coffee production challenges should be met. Years of laboratory research and hundreds of millions of dollars have been invested to develop “super varietals” – such as: Costa Rica 95 (AKA CR-95), Castillo, Lempira, Maracatu, Oro Azteca and Anacafe 14 – just to name a few. And if these don’t solve the problem, farmers are encouraged to “migrate production” to higher elevations, or to simply diversify to a different crop altogether. But while these recommendations might look simple on paper, they come with enormous economic, social and cultural costs.

Coffee is an  extraordinarily complex crop; and the coffee marketplace equally so. A farmer must juggle technical advice against his or her own context (soil type, elevation, average and extreme temperatures, sun exposure, scale of operation, organic practices, shade-cover, seed availability, etc.) with the hope and the prayer that the mix with a new varietal will result in equally or better final production and cup quality. And the confirmation of that ‘calculated guess” will come only three to four years after the upfront investment is made, and the first season of full production is off the tree.

extraordinarily complex crop; and the coffee marketplace equally so. A farmer must juggle technical advice against his or her own context (soil type, elevation, average and extreme temperatures, sun exposure, scale of operation, organic practices, shade-cover, seed availability, etc.) with the hope and the prayer that the mix with a new varietal will result in equally or better final production and cup quality. And the confirmation of that ‘calculated guess” will come only three to four years after the upfront investment is made, and the first season of full production is off the tree.

So when external advisors in the region began telling farmers they should swap out their traditional varietals in order to achieve greater climate resiliency, Manos Campesinas had good reason to pause on the side of caution. And we applaud their approach; there’s a lot at stake – both for them and for all of us at Coop Coffees.

Manos Campesinas was conceived in 2000 as an umbrella organization to provide direct export channels for a founding group of 150 farmers organized in 4 member associations, including Apecaform in San Marcos – one of Coop Coffees longest standing partners. Today Manos Campesinas serves the market and technical needs for 12 small-scale and organic coffee farmer cooperatives across the departments of San Marcos, Quetzaltenango, Atitlan and Chimaltenango, representing more than 1,200 farming families.

Manos Campesinas is fiercely independent and proud of its self-sustaining and fiscally-responsible business model. They avoid, as much as possible, needing external support from government agencies or international NGOs, which can all-too-often lead to north-south dependency and a short-term, “project-based” mentality. The association’s strategic values include commitments to social responsibility, quality, sustainability, gender equality, and environmental protection. They aim to be the first choice for customers around the world, and not only for their coffee quality, but also for the quality of service and the positive impact provided to their member communities.

Manos Campesinas is fiercely independent and proud of its self-sustaining and fiscally-responsible business model. They avoid, as much as possible, needing external support from government agencies or international NGOs, which can all-too-often lead to north-south dependency and a short-term, “project-based” mentality. The association’s strategic values include commitments to social responsibility, quality, sustainability, gender equality, and environmental protection. They aim to be the first choice for customers around the world, and not only for their coffee quality, but also for the quality of service and the positive impact provided to their member communities.

The majority of the coffee grown by Manos Campesinas members is high-altitude SHB (Strictly Hard Bean), with a diversity of coffee profiles, from the rich chocolatey coffees of San Marcos to the tart berry-like coffees of Atitlán. Manos tecnicos and farmers alike, have dedicated years of hard work to achieve and maintain their reputation for high and consistent quality.

Therefore, in the aftermath of the 2013 coffee crisis from the epidemic spread of leaf rust, or La Roya, the Manos Campesinas’ technical team decided to take the validation of “best renovation options” into their own hands.

“In Guatemala there’s a low level of investigation and research focused on the elements that directly impact coffee productivity and quality, especially when dealing with small-scale and organic plots,” explained Manos Campesinas Director Carlos Reynoso. “Our team has worked hard during the past three years to develop and employ our own internal process of experimentation and learning – adapted to the realities that our producer- members face on a daily basis.”

The trials began with an initial test-plot at the APECAFORM headquarter in Pueblo Nuevo de Tajomulco. The technical team evaluated the most popular varietals in the region, honing the experiment down to the top five varietals in terms of productivity, climate resilience and expected cup quality — to include: Bourbon, Costa Rica 95, Anacafe 14, Catuaí, Icatú. These varietals were then planted in plots belonging to five “model member farmers” located in five different cooperatives spanning the region of San Marcos: APECAFORM, Flor de Café, ACIPACU, APROCAFE and ACAS, located at different altitudes and subjected to different environmental and growing conditions.

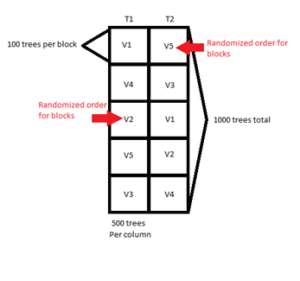

Each trial plot is co mprised of approximately 0.5 hectares and 1000 trees, divided into two columns with five “blocks” of 100 trees of each variety. Each column was subjected to two different organic fertilization methods (T1 commercial organic inputs vs. T2 locally produced organic inputs) and each block was planted in random order relative to each other’s location in the column. Data was collected for all parcels every 2 months. Out of each 100 tree “block” they would sample 43 trees at random and count leaves with the incidence of roya, ojo de gallo and stem girth. All data gathered would then be added to the overall results including production data upon the trees’ first harvests

mprised of approximately 0.5 hectares and 1000 trees, divided into two columns with five “blocks” of 100 trees of each variety. Each column was subjected to two different organic fertilization methods (T1 commercial organic inputs vs. T2 locally produced organic inputs) and each block was planted in random order relative to each other’s location in the column. Data was collected for all parcels every 2 months. Out of each 100 tree “block” they would sample 43 trees at random and count leaves with the incidence of roya, ojo de gallo and stem girth. All data gathered would then be added to the overall results including production data upon the trees’ first harvests

This initial work was conducted with support from the Coop Coffees and Root Capital Coffee Farmer Resiliency program, and additional support from other Manos Campesinas’ clients.

“Throughout this process, we have been tremendously impressed by the methodology and systematic approach that Manos Campesinas utilized to design the experimental plots and to gather information and results,” said Coop Coffees Green Coffee Buyer Felipe Gurdian.

Now three years into experimenting, tracking and evaluating the tolerance of these varietals to common disease such as “La Roya” (emileia vastatrix) and Ojo de Gallo (Mycena citricolor) against the productivity and general tree health, the team at Manos Campesinas was ready to put their first full harvest to the ultimate test – final cup quality – under the scrutiny of their primary clients.

Now three years into experimenting, tracking and evaluating the tolerance of these varietals to common disease such as “La Roya” (emileia vastatrix) and Ojo de Gallo (Mycena citricolor) against the productivity and general tree health, the team at Manos Campesinas was ready to put their first full harvest to the ultimate test – final cup quality – under the scrutiny of their primary clients.

In March, the Coop Coffees green sourcing and quality control staff, along with member roasters Peace Coffee, Higher Grounds and Third Coast Coffee, had the opportunity to participate in a cupping workshop and internal quality competition in San Rafael, Pie de La Cuesta, Guatemala. In order to leverage the learning opportunity of this event, we invited Coop Coffees producer partner representatives from neighboring regions of Guatemala and Southern Mexico to participate.

In March, the Coop Coffees green sourcing and quality control staff, along with member roasters Peace Coffee, Higher Grounds and Third Coast Coffee, had the opportunity to participate in a cupping workshop and internal quality competition in San Rafael, Pie de La Cuesta, Guatemala. In order to leverage the learning opportunity of this event, we invited Coop Coffees producer partner representatives from neighboring regions of Guatemala and Southern Mexico to participate.

“This year was the first full harvest from these trees,” said Coop Coffees Quality Lab Manager Matt Damron. “It was an honor and a great responsibility to be able to complement their work by providing our perspective on the final cup quality. One thing that was certain upon viewing some of the preliminary cupping results was that the varietal is not necessarily an end-all determinant for quality,” he continued, “many other factors relative to geography, growing conditions, plant care and fertilization methods, likely had a greater bearing on ultimate cup quality.”

“This year was the first full harvest from these trees,” said Coop Coffees Quality Lab Manager Matt Damron. “It was an honor and a great responsibility to be able to complement their work by providing our perspective on the final cup quality. One thing that was certain upon viewing some of the preliminary cupping results was that the varietal is not necessarily an end-all determinant for quality,” he continued, “many other factors relative to geography, growing conditions, plant care and fertilization methods, likely had a greater bearing on ultimate cup quality.”

Our final cupping result, reinforced the initial motivation for this experiment – reminding us that growing coffee is a complex endeavor… and even more so when you’re a small-scale organic farmer, living and producing in remote areas with a wide range of soil, climatic and agro-geological conditions.

Our final cupping result, reinforced the initial motivation for this experiment – reminding us that growing coffee is a complex endeavor… and even more so when you’re a small-scale organic farmer, living and producing in remote areas with a wide range of soil, climatic and agro-geological conditions.

This experience and these experimental plots now serve as an on-going teaching tool for member farmers, instructing them on the different physical characteristics of the varieties, examples of inputs required for optimal yields, and their potential resistance to common pests and disease. Moving forward, the technical team at Manos Campesinas envisions setting up the experimental plots as formalized learning facilities, where they can continue to test different production methods and practices and to teach and share some of the results generated from these experiments. Manos Campesinas will continue to gather production and cost information, and with that, will be able to provide more fully informed recommendations regarding field renovation to their members.

So rather than prescribing production recipes – Manos Campesinas appears to be on the best possible track by instilling a spirit of experimentation, adaptation and innovation amongst their producer members.

Author: Monika Firl

Apri 6, 2018